Political stability and absence of violence in Mozambique are in their lowest levels in two decades. And while Mozambique’s economy remains one of the most dynamic on the continent it is unclear how its main development driver – extractive sector, propelled by a boost in coal exports – will impact income inequality and the prospectives of future development in the country.

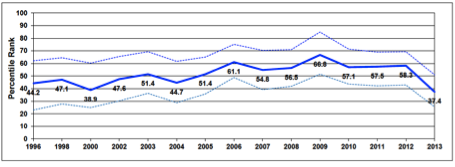

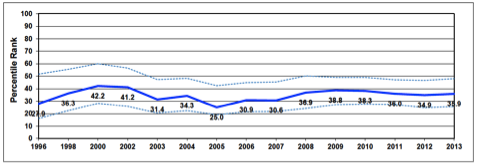

Political Stability and Absence of Violence

Source: World Governance Indicators

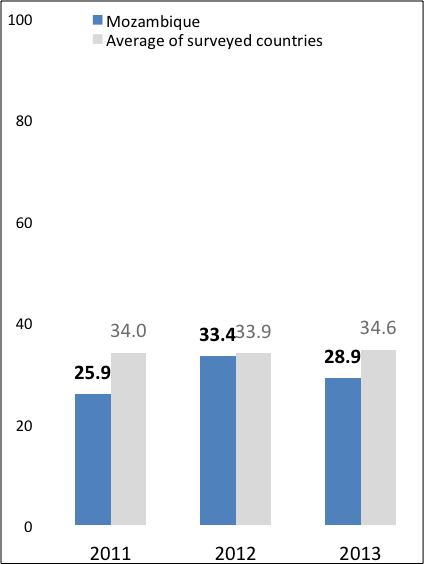

Mozambique is confronted with two major challenges that directly impact the energy sector as well as national security. First, as stated by the Minister of Energy, Salvador Namburete, in a visit to New York City last year, there is a fundamental capacity gap in the government structure. Mozambique ranks below the average among the 42 African countries analyzed; and the gap is increasing. The performance of the sub-index “capacity development outcomes” is even worse.

Africa Capacity Index

Source: Africa Capacity Building Foundation

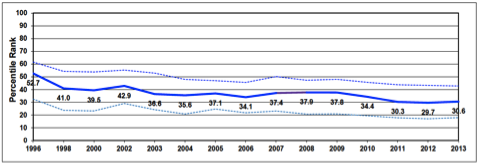

Not surprisingly, as the country tries to develop and governance becomes more complex, this lack of skilled technicians has a compound negative effect on government effectiveness.

Government Effectiveness

Source: World Governance Indicators

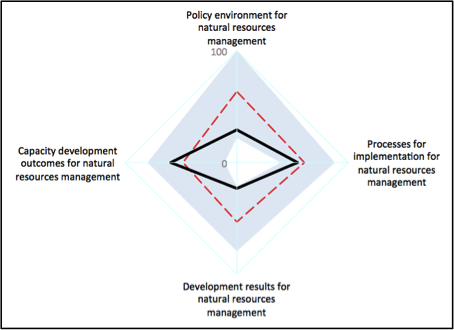

This situation is particularly detrimental for the energy sector: demands from multinational companies seeking to explore business opportunities derived from natural resources (e.g., gas and coal) place extreme pressure on the management skills of government units and personnel. Notably, Mozambique performs poorly in three out of four critical management skills and capacities in this strategic sector.

Natural Resources Management Index

Source: Africa Capacity Building Foundation

This is exacerbated by more cautious approaches to business relations and contracting, which result from negative experiences with Brazilian Vale and Australian Riversdale.

A source at ENI – the Italian multinational oil and gas company – in Maputo called for the creation of two types of training programs:

i) six-month short-term courses with a focus on specific technical skills such as: electrical, mechanical, food-preparation, driving, English-language, carpentry.

ii) three-year specialized degrees for the oil & gas industry in areas such as damming and water management, drilling, geology, engineering, industrial mechanics, electrical engineering, and ICT.

The paradox, however, is that donor commitment in support of the education sector is diminishing. In 2014, the amount of foreign aid to the education sector was less than 20% of the sector’s budget, down from 29% in 2009. In addition, the proportion of the total national budget allocated to education decreased from 22% in 2007 to 15.7% in 2014.

The second fundamental strategic priority for Mozambique is the new institutional and legal framework for the energy sector, in general, and oil & gas, in particular. According to the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, four of the ten economic freedoms in Mozambique worsened since last year, including trade freedom, investment freedom, business freedom and fiscal freedom. Overall, the score has declined by 0.2 points; the 22nd largest decline in economic freedom in the world.

Index of Economic Freedom

Source: The Heritage Foundation

If we look more specifically at the regulatory quality the scenario is even more problematic: there has been a consistent decline since 2009, except in 2013 when the figure slightly increased. Notably, 2009 was a general election year, at which time former President Guebuza was elected with 75% of the votes.

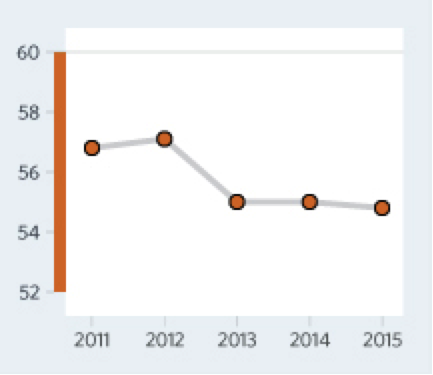

Regulatory Quality

Source: World Governance Indicators

In spite of the efforts of National Electricity Council (CNELEC) – the Advisory Board to the Government – to establish a modern legislation, and a more predictable and transparent licensing system, the country is yet to have a full-fledged regulator body. This situation imposes very important constraints to the most needed public-private partnerships for investment in infrastructure required to make production viable and develop new development corridors in the country.

The ENI source in Maputo pointed the following as the priority aspects of the regulatory body, which the government should focus on:

. Drafting and disseminating a clear national strategy for oil & gas.

. Designing domestic price and subsidy schemes that take into consideration: household income, access alternative energy sources, geographic dispersion, and estimated demand.

. Designing clear and non-arbitrary taxation schemes as a function of firms’ investment in social and local development.

. Determining in what combination of cash and in-kind the government will take its share of gas, so as to be most beneficial to Mozambique. And how this combination should change over time.

. Clarifying the multiple licensing processes associated with gas explorations and business operations. Currently the regulation is very ambiguous.

. Streamlining and accelerate the procedures for licensing, permits, and other legal procedures, since at the current pace, the 2018 production-start goal is in jeopardy.

. Designing incentive programs, associated with the mega-projects, so as to promote the development of competitive SMEs across the country (i.e., in Rovuma SMEs do not have enough information about business opportunities related to Anadarko’s and ENI’s development projects).

. Designing strong accountability structures, regulation’s enforcement mechanisms and monitoring systems to guarantee that all projects have a sustainability component built in, at the national, provincial, and district level.

. Expanding research in areas like: potential volumes, timing, and location of future development beyond Rovuma; size and location of domestic demand; transport tariff framework.

If these critical technical and skills gaps, as well as institutional voids, are not bridged, the government capacity to both benefit from its natural resources and implement distributive mechanisms across the country will continue to be undermined, human development jeopardized and national security threatened, as regular outbursts of violence in the country have shown.

Source: World Post