Italian energy giant Eni SpA has emerged in recent weeks as the only international oil company still pumping near capacity in war-torn Libya, helped by protection from militias and tribes secured by its local partners.

Libya’s security risks have crippled the efforts of rival oil companies such as Total SA of France, Repsol SA of Spain and Marathon Oil of the U.S., which have said they have suspended production onshore in the North African country.

The dangers have intensified in the past month with the rise of terrorist network Islamic State in Libya, a new risk in a nation that fractured after the 2011 ouster and death of dictator Moammar Gadhafi. Some of the country’s oil fields were left in ruins by attacks last month by gunmen who have allied with Islamic State.

So far, Eni’s operations through its partners have largely been spared in the fighting between an Islamist group of militias called Libya Dawn that controls the capital of Tripoli, and an internationally recognized government in the city of Baida, thanks to security arrangements struck on its behalf, according to people familiar with the matter.

In the nation’s northwest corner, an Eni pipeline carrying around 10% of Italy’s natural gas supplies sits near a jihadi training camp but is protected by a militia called Western Shield that is part of Libya Dawn, said Libyan officials and a Western security official. And to help ensure smooth operations at the Wafa field in Libya’s south, Eni’s local partners have hired youths in Zintan, a city allied with Libya Dawn’s rival in Baida, and militias drawn from the city are aiding with protection, according to a Libyan oil official and the Western security official.

“Eni is holding the stick in the middle,” said the Libyan official, using a rough translation for an Arab phrase about cultivating both sides.

An Eni spokesman said the company has no agreements with any militias in Libya. Eni declined to make an executive available for an interview. The company has said it has evacuated its staff from Libya’s mainland.

Its operations there are run by Mellitah Oil & Gas, a 50-50 joint venture between Eni and Libya’s National Oil Co. Bonatti, an oil-services company that works with Mellitah and has some of the last Western expatriates still working in Libya, helped secure some of the security arrangements, said people familiar with the matter.

Doing business in high-risk countries has been part of Eni’s portfolio since it emerged onto the international energy scene in the early 1950s when then-Chairman Enrico Mattei set the goal of ensuring Italian energy independence.

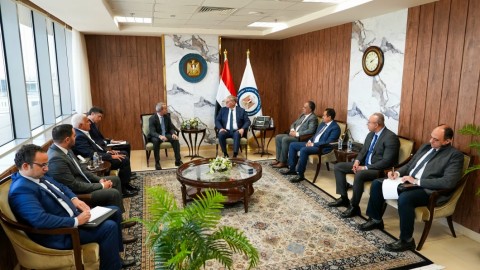

Eni, Italy’s largest company by sales and market value, is among the 10 biggest oil-and-gas companies in the world by revenue and is the largest western producer in Africa. That size has made Eni a de facto arm of Italian foreign policy. CEO Claudio Descalzi earlier this year was part of an official Italian delegation sent to Cairo to discuss the situation in Libya.

The relationships have helped Eni produce 240,000 barrels a day of oil equivalent, which includes gas production, in Libya last year and 300,000 a day in early 2015, by far the most of any company there. Eni now accounts for about a third of Libya’s oil-and-gas production compared with less than a fifth before Gadhafi’s death, according to figures released by Eni and the Libyan government.

“Eni has been operating in Libya for more than 50 years, much more than the other European oil companies, and it is easy to imagine that in that time they have made the contacts that now make it possible to coexist with some of the militias,” said Alberto Tonini, the head of the master’s degree program in Mediterranean studies at the University of Florence.

Other companies have generally arranged for security directly through Libya’s National Oil Co., Libyan officials said. Some of their fields, much of them in the central Sirte region, were the scene of devastating attacks last month.

Striking security deals with Libyan militias is a “risky strategy,” said Geoffrey Howard, a Libya analyst at Control Risks, speaking generally. The membership of local militias changes often, and some could be accused later of human rights abuses or of being connected to terrorists, he said.

“The proliferation of nonstate actors [in Libya] makes it increasingly complex to do business,” Mr. Howard said.

Eni also has benefited from the fact that many of its operations are offshore, an area not yet touched by the violence roiling Libya.

Onshore fighting has targeted the oil industry. In March, militants attacked a remote field in the desert, decapitating eight Libyan guards and kidnapping nine foreigners. A similar attack in February led to the killing of 12 Libyan and foreign oil workers. Damage to oil facilities could take months to fix.

It is about 7 miles east of a training camp of the Tunisian branch of jihadist group Ansar al-Shariah. The camp was initially for fighters joining Islamic State in Syria and is now focused on attacks in North Africa, according to a Western security official.

At the complex’s dock on the Mediterranean Sea a boat stands ready to whisk workers to safety.

“The assumption is that gun or mortar fire would be heard when an attack started at the gates to the plant and the workers would have time to run to the boat that would take them to safety,” said a person briefed on the plans.

Eni declined to comment.

The unraveling of Libya has special resonance in Italy—just 315 miles away across the Mediterranean—because of the country’s proximity and their long and intertwined past. Italy occupied its southern neighbor for 30 years at the beginning of the 20th century, and the countries’ commercial relations go beyond oil and gas.

Salini Impregilo, Italy’s largest general contractor, had to abandon seven commissions—including building a highway, airport and conference center—last year worth about $2 billion because of safety concerns. Finmeccanica, the Italian space and defense company, and Italy’s aviation authority have suspended contracts there as well.

Source: The Wall Street Journal