By Stephen Fullerton, Research Analyst, Middle East and North

Africa Upstream Oil and Gas

Not long ago, Egypt’s gas industry was in crisis. Production fell by a third in the three years to 2015; a top 10 LNG exporter in the prior decade, the country had by then become a top 10 importer. Nearly all available gas had to be diverted by the government to serve the domestic market.

As a result, export revenue dried up, the cost of gas imports soared and there was insufficient cash to pay contract commitments to E&P investors. Arrears ballooned to US$7 billion, and producers were becoming uneasy.

Today, happily, things are very different and investment is flooding back in. What happened to turn things around?

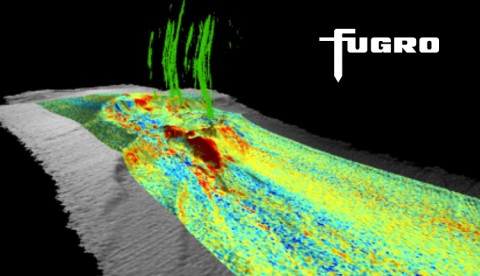

First, Egypt is one of the lucky countries geologically, endowed with enormous resource potential which has fostered an active industry for 150 years. Attention has shifted this century from traditional onshore heartlands and the Gulf of Suez, to the deeper water gas discoveries in the Nile Delta and Mediterranean. Eni’s spectacular giant Zohr find in 2015 (22 trillion cubic feet) not only opened up a completely new play in the wider region, but really put Egypt back on the global E&P map.

There is plenty more to play for. We estimate Egypt’s current resources at 3 billion barrels of liquids and 61 trillion cubic feet of gas. There is likely the same still to come in gas. Our yet-to-find estimates are around 1 billion barrels of liquids and 45 trillion cubic feet of gas, which puts Egypt fourth in the global rankings of prospective conventional offshore basins behind Brazil, Gulf of Mexico, and Nigeria.

An experienced senior Egyptian geologist I met in 2013 told me 200 trillion cubic feet will eventually be found in Egypt’s Mediterranean waters.

Second, the investment climate is much improved, in spite of production sharing contracts (PSCs), which typically have among the highest government shares around. The key has been a canny approach in dealing simultaneously with gas pricing and PSC terms for individual projects. For years, Egypt’s fixed gas price of US$2.73 per million cubic feet discouraged exploration and development, especially in the more prospective but higher cost deep water.

The government recognized the challenge of attracting capital post-2014 and set about providing returns that would work for investors. Gas prices for offshore developments have been negotiated project-by-project these last few years. BP’s large-scale West Nile Delta project, which had languished in the front-end engineering and design stage for years, demonstrated this new, flexible approach to terms, leading to project FID in 2015.

The country has also emerged as an unlikely global leader in project execution. Eni’s giant Zohr project was brought onstream on budget and just 30 months after discovery – a world record for a development of such scale. Internal rates of return (IRRs) for West Nile Delta and Zohr are both in the mid- to high teens by our calculation. The upshot is that Egypt’s gas sales will return to last decade’s levels of around 6 billion cubic feet per day this year, and climb to nearly 8 billion cubic feet per day by 2020 as West Nile Delta and Zohr reach plateau.

Dealing with the payment arrears has helped restore confidence across the industry. The government has tapped a US$12 billion IMF loan to pay off creditors, reducing the liability in each of the last five years – and it will be wiped out completely by the end of 2019.

Licensing processes have been sharpened up, with regular bid rounds, relinquished acreage recycled quickly and new opportunities to fuel interest among prospective investors.

Egypt has assumed unprecedented importance in Eni and BP’s global portfolios in the short passage of time since 2015. It is now the third most important country position for Eni by value at US$9 billion, NPV10; and fourth for BP at US$11 billion, NPV10. Rosneft’s acquisition of 30% of Zohr in 2016 suggests that the resource potential will draw other big IOCs and NOCs into Egypt and the wider East Mediterranean gas play.

Many other countries, including mature upstream provinces, are still struggling to attract investment after the downturn. Egypt’s pragmatism towards its big projects shows that with will on both sides it is possible to get capital – and production – flowing again.