By Ahnie Litecky

The vast wealth of hydrocarbons that lie beneath Egyptian waters in the Mediterranean Sea has recently attracted international attention and possibly provoked envy of some countries. While massive finds in the eastern Mediterranean areas have intensified interest in expanding exploration activities in the region, Egypt’s future may be promising when looking at the country’s northwestern coast as well.

Scientific research has estimated that Egypt holds huge reserves in its western deep waters, which may help the country to progress towards energy security. This scenario may be realized if companies continue investing in exploration activities.

Success of BP’s West Nile Delta Project

Exploration of Egypt’s offshore gas potential began in the early 1960s. By 1975, the country started investigating deeper waters in the Mediterranean and ramped up exploration twenty years later. Egypt’s northwestern coast, defined here as stretching from Alexandria to the Libyan border, has been mostly parceled out for development through the Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company’s (EGAS) concessions. Areas closer to the Nile Delta have already been shown to contain substantial gas reserves, particularly within BP’s West Nile Delta project.

A year ago, BP pledged a $12 billion investment to develop gas resources in its West Nile Delta project, which contains two concessions known as North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deep Water, in the waters off Alexandria. Today, BP holds majority interests in the two concessions of almost 83%, and its partner, RWE DEA, holds the remaining shares.

BP plans to develop the West Nile Delta Project in two phases. Phase One involves exploring and operating five major fields: Taurus, Libra, Fayoum, Giza, and Raven. According to the current schedule, the fields should be made operational by 2017. Additional five fields will be developed later. Last July, BP and DEA awarded a contract to subsea engineering and construction company, Subsea 7, to begin working on infrastructure to develop hydrocarbons from nine wells in the Taurus and Libra fields. In January this year, Subsea 7 agreed to develop the Giza, Fayoum, and Raven subsea fields beginning in 2017.

By 2017, BP aims to produce about 1.2bcf/d, which will equal about 25% of Egypt’s current gas production. The company estimates that additional 5tcf to 7tcf of gas will remain in undeveloped fields.

Previously, in March 2015, BP’s North Africa Regional President, HeshamMekawi, stated in a press release that BP planned to double its current gas supply to the Egyptian domestic market in the next four years. According to Mekawi, the West Nile Delta Project “is a strategic project for BP and will play a key role in helping to secure Egypt’s energy supply for many years to come. This deal is another example of our commitment to help unlock Egypt’s oil and gas potential through continued investments.”

BP’s Mekawi told Reuters in January 2016 that the significant gas finds off Egypt’s coast “give a big incentive to the players who are here and maybe others considering investing in Egypt to do more.” He also said that “there is still a lot of gas to be found in Egypt in the Mediterranean.”

Other companies exploring concessions in the northwestern Mediterranean coast, however, have not been so lucky. Edison’s joint concession in the SidiAbd El Rahman offshore block, just south of BP’s West Mediterranean Deep Water block, turned up a dry exploratory well in 2009. One of Edison’s partners, PTT Exploration and Production Public Co., continued exploration work until 2011, but found nothing substantial. OMV won a concession for the deep water Obaiyed block, just offshore from the town of Matruh, in 2006, but the company relinquished the block in 2011 after assessing area’s low potential. Statoil had concessions for Ras El Hekma and neighboring El Dabaa, just east of the Obaiyed block. In 2011, the company also reported a dry well in the El Dabaa block and allowed its licenses for both blocks to expire in the same year.

Promising Hydrocarbons Off Northwestern Shores

Despite the somewhat limited hydrocarbon finds off northwestern Egypt until now, which have been mainly restricted to BP’s West Nile Delta Project, there is still a good reason for oil and gas companies to expand their westward exploration. Multiple studies conducted by scientists such as A. Maravelis or G. Tari, have argued that huge reserves of hydrocarbons are waiting to be discovered in the deep waters off Egypt’s northwestern shores. Greek researchers contended in the Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, published in 2013, that the area could potentially rival other gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean.

Northwestern Egypt’s offshore region can be divided into three geological domains of interest here: theMatruh Canyon, the shelf area, and the Herodotus basin.

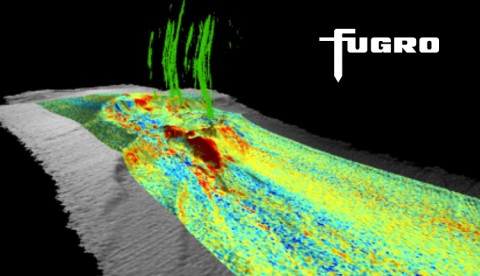

The Matruh Canyon is a rift basin that extends north to northeast from the Western Desert into the deep waters of the Mediterranean. It lies within the Matruh Basin. A nearby onshore well has demonstrated significant gas and oil shows, which, combined with gas chimneys and active mud volcanoes in the area, provide a strong prediction of a potential hydrocarbon find offshore. Also, the narrow shelf area, which hugs the Egyptian coast from the Libyan border to the Egyptian town of Marina El Alamein, can be linked to onshore discoveries and may hold hydrocarbon deposits.

However, the much larger Herodotus Basin has demonstrated the most promise. The Herodotus Basin, with an area more than 130,000 square kilometers, is located in the deepest part of the southeastern Mediterranean. The basin is bounded by the Nile Delta Basin to the southeast, the shelf area and Egypt’s Western Desert to the south, and the Levantine Basin to the east. Libyan waters are located in the west, and in the north lay the Mediterranean Ridge and Crete. The Herodotus Basin is divided into Greek, Cypriot, and the Egyptian Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ).

A wealth of scientific studies have shown that the basin appears to have huge oil and gas potential, including the probability of large stratigraphic traps and functioning petroleum systems. Of course, significant discoveries in neighboring areas, such as BP’s West Nile Delta Project, which straddles the Herodotus Basin and the Nile Delta Cone, as well as the Aphrodite, Tamar, and Leviathan finds, also contribute to the likelihood that there are similar reserves in the depths of the Herodotus Basin.

In 2013, a collective of Greek researchers concluded in the above-mentioned study that the Herodotus Basin has at least the same amount of gas and oil as the neighboring Levantine Basin. As mentioned above, their published findings were based on a combination of seismic data, petroleum geology, basin comparisons, and surrounding geological structures. If these researchers are correct and the Herodotus Basin has resources volumes close to the resources of the Levantine Basin, then development of the area could have an enormous impact. The US Geological Survey has estimated that the Levantine basin holds a mean of 1.7b barrels of recoverable oil and a mean of 122tcf of recoverable gas.

Challenges to Egypt’s Western Mediterranean Exploration

As Egypt’s northwestern offshore region is believed to hold great promise as a hydrocarbon motherlode, it is unclear why the area has not yet been exploited. One major challenge to unlocking the energy potential of the Herodotus Basin is the area’s extremely deep waters. Area boundary depths range from 1,000 meters to more than 3,000 meters. Ultra deep water, which is water depths of more than 2,000 meters, poses particular challenges that make oil and gas exploration technically and financially demanding. Drilling and completing wells in ultra deep water faces funding complications, and technical challenges that include weather, salt domes, adverse temperatures, and high pressure. However, advances in technology and expertise have improved seismic surveying and deep water drilling techniques, which now make exploring the resources of the Herodotus Basin an expensive, but a real possibility.

Another challenge that has so far curtailed exploration of Egypt’s northwestern Mediterranean subregion is the limited geophysical 2D and 3D seismic data coverage. 2D surveys were conducted in 1999, 2005, and 2007, however, the subsurface images are generally of a poor quality. In June 2015, Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS), a Norwegian marine geophysical company, was contracted by EGAS to assist in “the largest seismic oil and gas exploration project in the Mediterranean,” according to a PGS press release. The Norwegian company also stated that “Egypt’s Mediterranean Sea offers exciting opportunities for oil and gas companies who would like to evaluate a relatively unexplored area in a region with significant hydrocarbon potential.” PGS plans to reprocess existing 2D data and conduct new seismic 2D data acquisitions to enable a full assessment of the petroleum system in an 80,000 square kilometers area encompassing the Herodotus basin, the shelf area, and the Matruh basin. The collected data will be used to plan a future EGAS’s licensing round, tentatively scheduled for 2017.

Explore or Ignore?

The Egyptian government is betting that foreign companies will decide to invest in further exploration of northwestern Mediterranean waters, as plans for the 2017 bid round and recent efforts to lure investors have shown. The government has to contend with a challenging economic situation that could potentially hinder exploration, but so far all indications point to a careful increase in exploration activities. Any major hydrocarbon find in Egypt’s northwestern Mediterranean would have a considerable impact on the country’s economy and energy future.

Investment rates in exploration are most recently rebounding after several troubled years that Egypt has witnessed. In November 2015, the then-Minister of Petroleum, Sherif Ismail, told the local press that the number of new areas explored for oil and gas decreased from 53 in 2010 to just 27 in 2013. There were no new concessions granted in the two years after the 2011 revolution. However, the 2014 and 2015 EGAS bid rounds attracted an impressive array of international investments, which indicate that companies are increasingly optimistic about exploring in Egypt, despite the volatile energy market.

The Egyptian government is trying to create a hospitable atmosphere for investment, a tactic which has boosted foreign investors’ trust in Egypt’s oil sector. According to Daily News Egypt, foreign companies plan to invest approximately $7.5 billion in oil and gas research and exploration in 2016. There are currently 108 joint ventures made up of foreign, Egyptian, and Arab companies, and additional 62 research and exploration companies that are working directly in Egypt. Egypt finalized 15 new exploration deals in January 2016 and is currently working on three major oil and gas deals worth $9.2 billion.

Given that many oil and gas companies have responded to the economic downturn by reducing investment in exploration activities, the above outlined figures suggest a rather impressive dynamic in Egypt. In the previous year, energy companies issued approvals for a limited number of projects, with no intention to assess the tactics considering the level of global oil and gas prices. Foreign companies’ investments are now targeting merely major projects, promising highest profits. Minor or not yet developed projects have been paused or cancelled altogether. Rystad Energy, an Oslo-based consultancy firm, predicted that in 2016 worldwide oil and gas investments will fall to their lowest levels in the last six years.

The Future of Egypt’s Northwestern Offshore Development

In Egypt, however, there are several incentives for energy companies to invest in the country’s offshore exploration right now, according to Dr.DiaaNoureldin, an economics professor at the American University in Cairo, and an advisor to the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies, who recently spoke with Egypt Oil & Gas. The country’s Mediterranean waters are strategically located to serve the energy needs of Europe and Turkey, especially after Europe becomes an open market in 2020. Companies can also work with the Egyptian government in negotiating favorable deals based on the currently low average gas prices.

The economic implications of additional hydrocarbon finds in the Mediterranean are huge and could go a long way towards creating a more favorable trade balance in Egypt, according to Noureldin. New oil and gas discoveries would help decrease the country’s reliance on natural gas imports and help “create some form of certainty about Egypt’s medium-term growth outlook,” he said. Estimated improvement in country’s growth rates encourages foreign direct investment, not just in oil and gas industry, but in other sectors as well.

Amr Mostafa, Vice Executive Chairman for Operations at the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation, said in a speech at the Builders of Egypt Forum in early March that Egypt aims to be self-sufficient in fuel supplies by 2020. Mediterranean hydrocarbon discoveries could propel Egypt towards the goal of energy self-sufficiency.

With the stability of additional gas resources, the Egyptian government could remove gas subsidies that have encouraged consumption to skyrocket over the past few years. Current energy consumption in Egypt is “not balanced, not optimal,” argues Noureldin. If the government removes subsidies, then consumption would hopefully settle into a more sustainable pattern. However, Noureldin cautions that any major gas discoveries could potentially have the opposite effect, at least in the short-term. “My worry is that it may delay the process of moving to a balanced energy mix,” said Noureldin. The Egyptian government will have gained a “breathing room to delay subsidy reforms.”

Egypt’s northwestern offshore areas, with potentially rich hydrocarbon finds, are a possible ticket for companies looking to invest in promising exploration activities. The Egyptian economy would benefit hugely from the stability of additional gas fields. The roadblocks to development: technology, data, and low oil prices, are surmountable, which would make Egypt’s northwestern Mediterranean the next frontier of offshore exploration.